At the heart of these histories is a story that has fascinated me since I was a child, when I read and re-read a fictional account of the battle of Thermopylae in which a small force of Greek soldiers, led by the Spartan Leonidas, held up the advance of the Persian army long enough for the Greeks to ready the defence of Athens and the Peloponnese. It’s a story that has been told and retold again, including in a fairly recent film, 300, Rise of an Empire.

My recollection of this fictional account is a bit faint after all these years, but the histories show that the novel was clearly exaggerated with respect to some details of the battle of Thermopylae in which these men’s lives were sacrificed. In my memory the novelist also changed the date of the battle of Marathon to make the whole story more dramatic, ending the novel as the runner arrives at Athens after Marathon, with the news of victory. In Herodotus’ account the battle of Marathon takes place a few years earlier than Thermopylae, not after it.

Herodotus’ The Histories presents a relentlessly detailed account of the classical and pre-classical history of the eastern Mediterranean including some of the myths and legends of Greece, Persia and Egypt, and is divided into 9 books, each looking at a different period of time or geographical location.

The first book examines the way the conflict between Persia and Greece began. There are echoes of the story of Troy in the abductions of women that take place, and the story of the wealthy Croesus seems to be a place where myth meets reality. He is a man of ambition and decides to extend his empire to the east, which brings him into contact with the growing Persian empire under Cyrus. Cyrus responds by moving into Croesus’ Lydia (now partly Turkey) and conquering not only Croesus, but the Ionian Greeks settled along the coast.

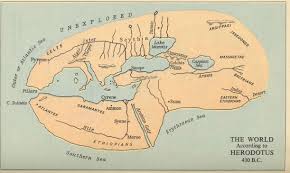

Book 2 is a history of Egypt. It is extensively detailed and some of Herodotus’ comments on the culture, history and geography of Egypt are especially interesting. For example Herodotus hypothesises about the source of the Nile, the size and shape of the world and the whole continent of Africa. He raises the question of whether it is possible to sail round Africa, and whether anybody had, recounting a story of men who found the sun rising on the wrong side of their boat as they journeyed on. Herodotus is sceptical about this, but it rings true to a modern reader.

Books 3 and 4 describe the growth of the Persian empire, including the conquest of Egypt by Cambyses, and excursions to the north into Scythia by Darius. Here myth and legend again become inextricably linked as factual knowledge about these northern areas was quite scarce. In books 5 and 6 Herodotus describes Darius’ excursion into Europe. This is in the end a failure. The Persians are expelled, and Darius dies before he can organise another expedition, leaving Xerxes to take over the reigns in books 7 to 9, which detail the events of his campaign.

The Landmark Herodotus is a clear presentation of this history. There is a series of detailed maps and footnotes so that with patience the reader can follow the progress of the armies, and discover the different parts of the world subject to Greek and Persian influence. Following Xerxes progress around the coast of the Aegean, or looking at the different parts of Asia subject to Persian rule was fascinating. I have to say that I’m a sucker for these kind of maps which have no real practical purpose or use – as one of my sons says, they are just cramming my brain with useless information!

There are several appendices to The Landmark Herodotus, and these fill in the gaps in Herodotus’ account, for example describing Spartan life and culture in detail, looking briefly at key dialect issues or considering the accuracy of Herodotus’ portrayal of Egypt. I mostly skimmed through these. There are also illustrations in black and white showing ancient implements or weapons, or presenting diagrams and illustrations of, for example, fortifications. These are all interesting.

For the more casual reader each section is accompanied in the margin by a clear and brief summary of its contents , and many students would benefit from, and even rely on this, as it allows the reader to quickly skim sections and retrieve significant information. The histories are also divided into numbered sections which allow the reader to identify footnotes with ease.

The Landmark Herodotus was a gift, and not a book I would have chosen myself, being rather academic and of quite a daunting length. It’s not without fault – some footnotes are missing and it was quite fun to notice these – what a geek I am!

Nevertheless it’s a great resource for any student of the classics, and whilst I wouldn’t recommend everyone to read The Histories word by word as I did, there are certainly many interesting comments and pieces of information. As a landmark document showing the first recorded attempts to offer both a factual history, and a scientific and sceptical account of the Greek world, Herodotus is certainly worth a look!!

In his book Persian Fire Tom Holland offers his account of the conflict between Greece and Persia which he sees as epitomising the great divide between Asia and Europe embodied in today’s clash of Christian and Muslim civilisations. This is a much more accessible version of events, but not to everyone’s taste.